Searching Library Databases

This guide contains a variety of suggestions and how-tos for advancing your database searches beyond simple keyword searches. These methods take some time to learn, but they make your searches more efficient and help you find more relevant results.

This guide covers:

- Boolean Operators

- Refining Search Results

- Subject Headings

- Brief Overviews of the Following Databases:

Why isn’t Google Scholar covered in this guide? Google Scholar isn’t a library database and works a bit differently from them. See this tutorial for help using Google Scholar, and this guide for an overview of the differences between Google Scholar and library databases. If you need help with a database not featured in this tutorial, feel free to ask a librarian.

Boolean Operators

Boolean operators are an excellent way to improve the relevance of your keyword search results. Booleans work in OneSearch as well as databases. Useful operators are described below:

| Operator | Example | Search Effect |

| AND | Macbeth AND witchcraft | Will only return results that contain both “Macbeth” and “witchcraft.” AND narrows searches. |

| OR | cancer OR carcinoma | Will return results that contain “cancer,” “carcinoma,” or both terms. OR broadens searches. |

| NOT | cloning NOT sheep | Will return results that contain “cloning” but not those that also contain “sheep.” NOT narrows searches. |

| ” “ | “online education” | Will return only results that contain the exact phrase “online education,” not those that contain “online” and “education” separately. |

| * | interact* | Will return results that contain “interact,” but also results that contain “interactions,” “interactivity,” “interacting,” and other variations. |

| ? | wom?n | Will return results with any one letter in the place of the question mark–in this case, results that contain either “woman” or “women.” Is also useful for searching singular or plural words, as well as American and British spellings. |

Boolean operators are processed from left to right. If you’re using multiple types of operators, parentheses are the simplest way to make sure the database processes your search correctly. For example:

(Myanmar OR Burma) AND colonial* AND (law OR legal)

Let’s break down this search:

- (Myanmar OR Burma) finds results that use either or both names for the country.

- colonial* returns “colonial,” as well as “colonialism,” “colonialist,” and any other variations.

- (law OR legal) helps find results that discuss either law, legal systems, legal structures, and/or legal frameworks.

The parentheses make sure that related concepts are processed together, and the ANDs make sure that only results that contain every element of the search are returned. See the search run in the Historical Abstracts database.

(“skin cancer” NOT melanoma) AND Australia*

Let’s break down this search:

- (“skin cancer” NOT melanoma) finds results that contain the exact phrase “skin cancer” but aren’t about melanoma, a certain type of skin cancer.

- Australia* finds results that contain “Australia,” as well as results that contain “Australian” or “Australians.”

The parentheses ensure that “skin cancer” and melanoma are processed together, and AND joins the two elements of the search. See the search run in PubMed.

poet* AND modernis* AND politic*

Let’s break down this search:

- poet* finds results that contain “poets,” “poetry,” “poetics,” or so on.

- modernis* finds results that contain either “modernism” or “modernist.”

- politic* finds results that contain “politics,” “political,” or so on.

The ANDs join all search elements together. See the search run in Project MUSE.

Booleans and Advanced Search

Boolean operators work very similarly to advanced search operators found in OneSearch and library databases. In addition, advanced searches allow you to pre-filter your results–for example, by author or publication date.

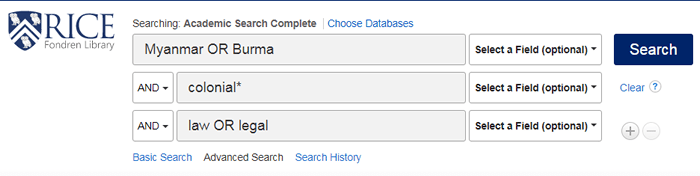

You can use the boxes in an advanced search interface like parentheses, with Boolean operators both within the boxes and between them. One of the previous examples can be rendered in Academic Search Complete like this:

The database will process “Myanmar OR Burma” before “AND colonial” since it processes each line on its own. See the search run in Academic Search Complete.

Refine Results

Once you run a search, most databases offer you some means of refining your results. On the left side of a search results page will be a list of facets–that is, characteristics–that you can select to filter the results displayed to only those that meet certain criteria. Refining results in databases works very similarly to refining results in OneSearch, which is discussed here.

Databases vary in the facets they offer. Two databases are discussed below.

Web of Science

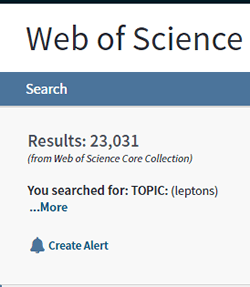

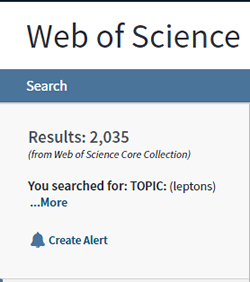

A topic search for leptons (the subatomic particle) in Web of Science produces over 23,000 results.

The following panel appears on the left of search results in Web of Science (note that numbers and top-ranked “Web of Science Categories” will vary based on the search terms.)

You have the option to focus on papers the are highly cited in the field, currently “hot” in the field, open access, or are linked to associated data.

Other options for refining results include publication year, category (equivalent to subject here), document type, organization (primarily universities) affiliated with the results, funding agencies, authors, source titles (primarily journal titles), conference titles, countries of origin, languages, and more.

Say you’re looking for articles (Document Type) published within the past two years (2017-2019, Publication Years) in English (Language). Applying those three filters brings the search results down to just over 2,000.

PsycINFO

A general search for language acquisition on PsycINFO produces over 20,000 results.

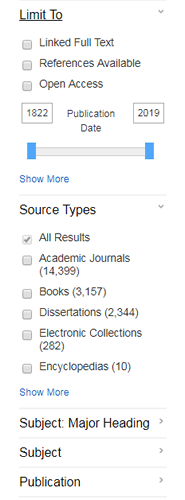

PsycINFO offers a wide variety of facets to refine results.

As a subject-specific database, PsycINFO includes filters specific to psychological studies, such as the age or gender of study participants and the methodology and tests and measures used.

Other available facets, similar to those found in Web of Science, include source types (such as books or dissertations), subjects covered including the articles’ major subjects, publication, publisher, and language. A slider bar can be used to specify a range of publication dates for results.

Let’s say you’re looking for academic journal articles (Source Type) published in the last five years (since 2014, Publication Date) about foreign language-learning (Subject: Major Heading) in adults (Age) that use brain imaging (Methodology). Applying all of those filters decreases the search results to only 22.

Sometimes, you may apply so many filters that you receive only a handful of results. In these cases, you may want to consider which filters are really necessary. Most databases keep a list of current filters at the top of the facets bar, making them easy to remove from your search.

In other cases–such as in the Web of Science example above–you may still have thousands of results after applying filters. In these cases, you probably want to rework your original search terms to be more specific, then apply filters.

Subject Headings

Most databases categorize their books, articles, or other resources by subject. This is done by assigning a subject or subjects to an item from a predetermined list (a controlled vocabulary or “thesaurus”) of terms, called subject headings.

You can filter your search results by subject headings, as is discussed in the PsycINFO example above. But you can also search using the list of subject headings. Three examples–Compendex, PubMed, and PsycINFO–are shown below.

While searching with subject headings can be useful, keep in mind that they are not available for every database, and some databases use much more specific subjects than others.

Compendex

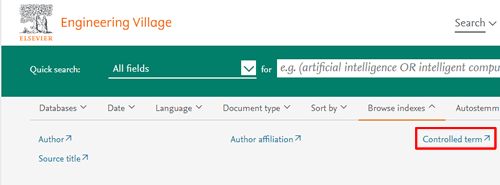

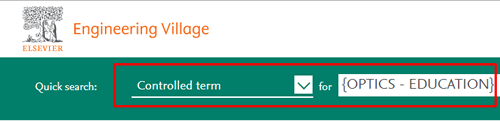

1. Click “Browse indexes” from Compendex’s homepage.

2. Click “Controlled term.”

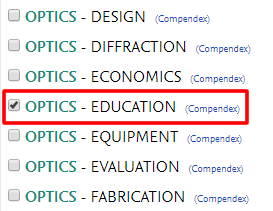

3. Browse terms or search for terms in the Compendex controlled terms (subject headings) list.

4. Check the box to the left of the term or terms that interest you.

5. Search. Each term you check is automatically added to the Compendex search bar.

PubMed

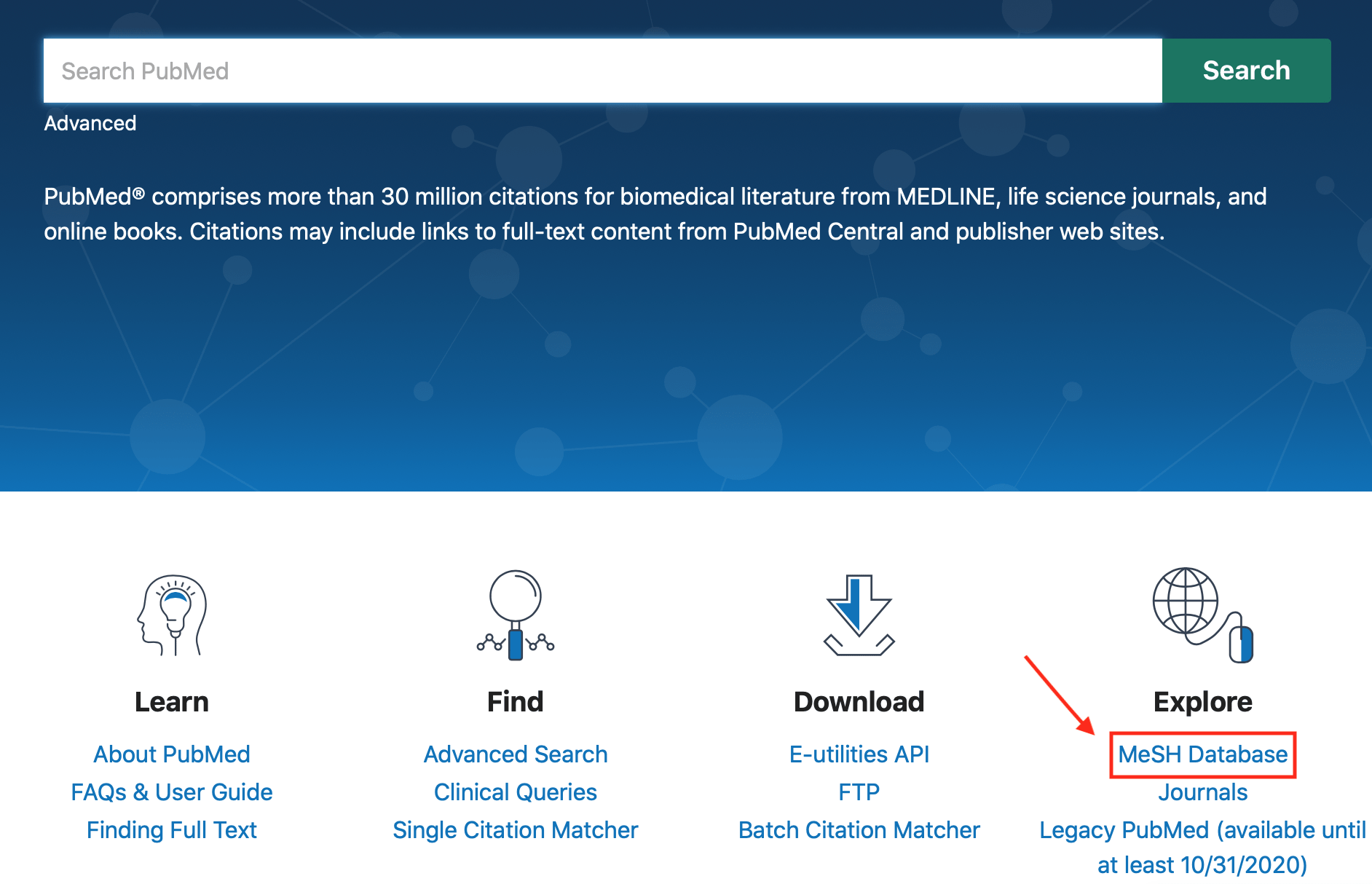

1. Scroll down and select “MeSH Database” under the “Explore” category.

(MeSH stands for “Medical Subject Headings.”)

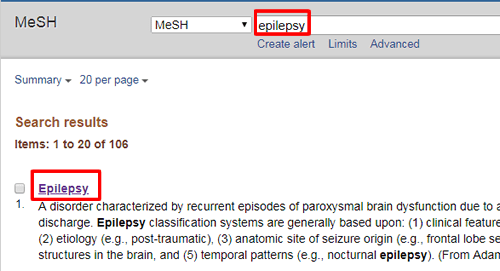

2. Search for a term that interestes you.

If the term is a MeSH term, it will appear. If not, the database will supply synonymous or related MeSH terms.

3. Scroll down to browse other potential MeSH terms to use.

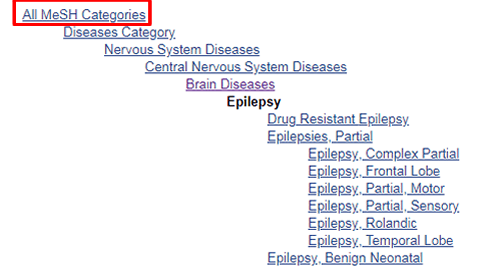

MeSH terms are arranged in a tree from general to specific. You may see a more specific term you’d like to search.

If you want to browse every MeSH term, click “All MeSH Categories.” You can find this tree by selecting one of the search results and scrolling down past the search builder options.

4. Click “Add to search builder” below the PubMed Search Builder at the top right of the page to add a MeSH term to your search.

5. Search.

PsycINFO

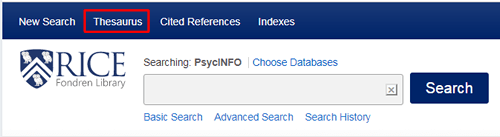

1. Click “Thesaurus” from PsycINFO’s homepage.

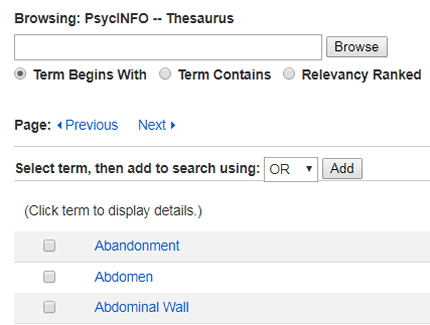

2. Browse subject headings or search for terms.

3. Click on a term that interests you.

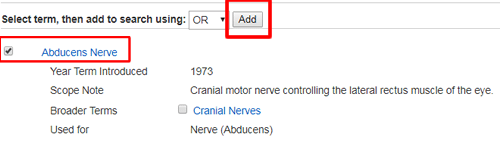

Each term has a page that details which year the term was introduced to PsycINFO’s subject headings, what exactly the term covers (Scope), any broader or narrower terms that can be used to retrieve more related information, and any synonyms for the term.

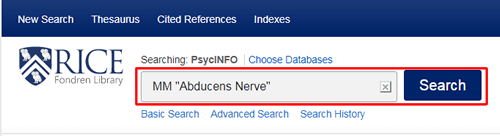

4. Check the box to the left of the term and click “Add” to add the term to your search.

If there are already one or more terms in your search, you will also have to select a Boolean operator to connect the existing term(s) with the new one.

Database Overviews

Academic Search Complete

Academic Search Complete is a broad database with materials in business, the humanities, STEM, and the social sciences.

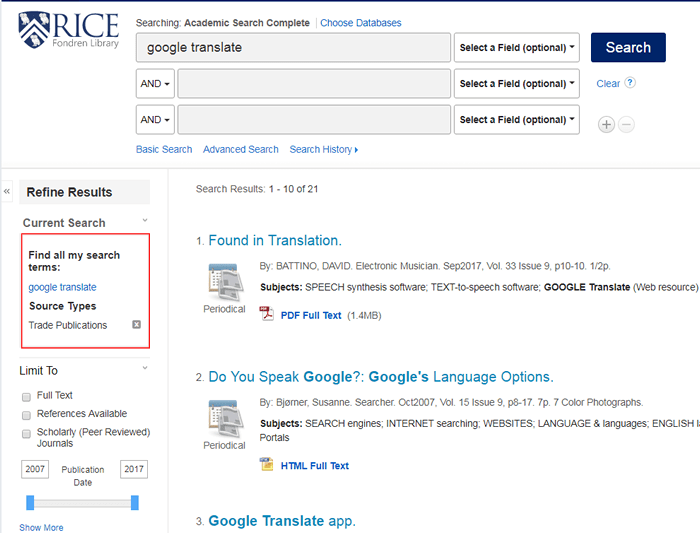

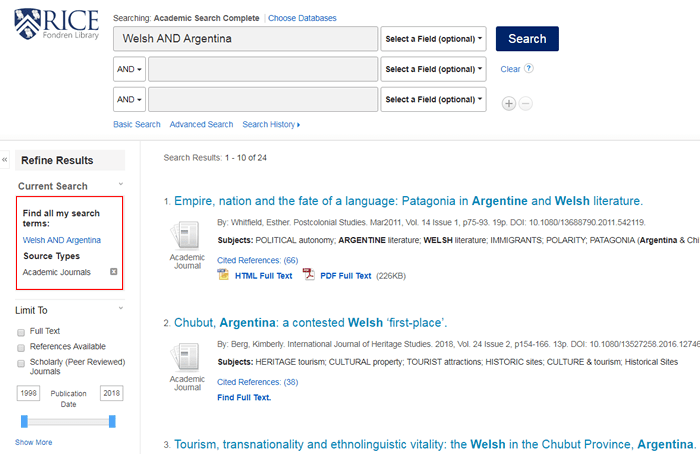

One of Academic Search Complete’s useful features is its ability to conduct business-related searches. You can search for companies by name, DUNS number, or ticker symbol, as well as industries more generally by their NAICS codes. Search results can easily be narrowed to trade publications under the “Source Types” facet (similar searches are available in the database, Business Source Complete).

Additionally, Academic Search Complete can search for geographic terms and people who are associated with an item but did not author it.

Two example searches are shown below. One is a business-related search refined to “Trade Publications,” and one is a more academic search refined to “Academic Journals.” Both searches produce relevant results.

Compendex and Inspec

Compendex and Inspec are two closely related databases from Engineering Village. Compendex indexes engineering literature, while Inspec indexes literature for physics, computer science, electronics, and information technology.

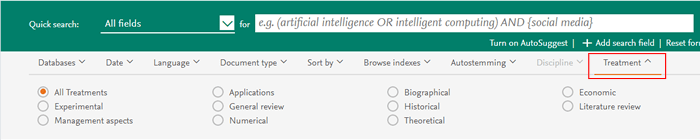

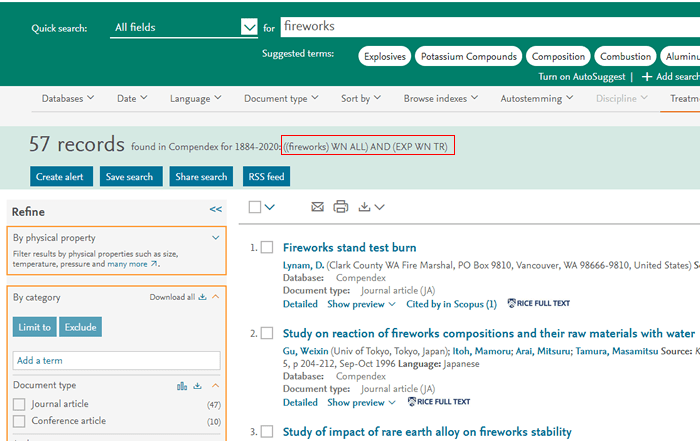

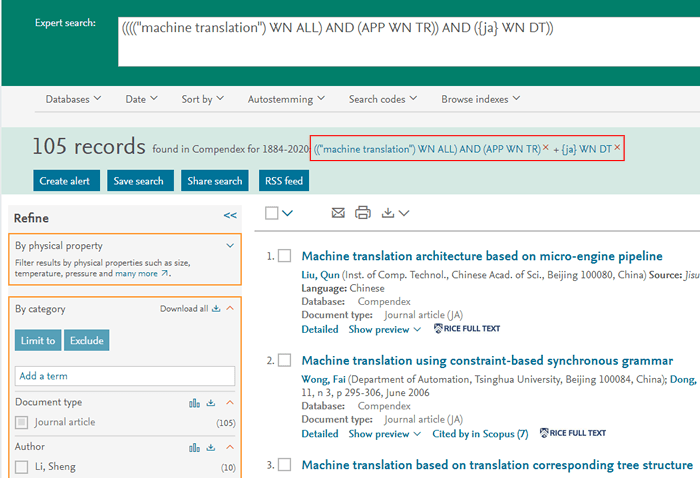

Compendex and Inspec contain conference articles and proceedings, reports, standards, and some patents in addition to scholarly articles and books. One unique feature is the ability to search for materials by their “treatment”–economic, historical, theoretical, applications, or otherwise–of a given topic.

Below are two examples of this search function. The first is for experimental treatments of fireworks, the second for journal articles about applications of machine translation. Both searches produced a manageable number of results (57 versus 1,001 with the filter for fireworks, 105 versus 1,576 for journal articles about machine translation) with titles related to the treatment in question.

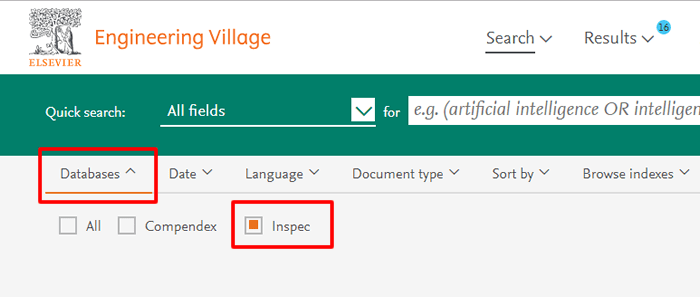

By default, the Engineering Village interface only searches Compendex. To search Inspec, click on the “Databases” tab under the search bar and select “Inspec.”

It is possible to search Compendex and Inspec at the same time by checking the “All” box.

Historical Abstracts

Historical Abstracts indexes resources related to history from 1450 to the present. However, it excludes American and Canadian history, which can be found in America: History and Life.

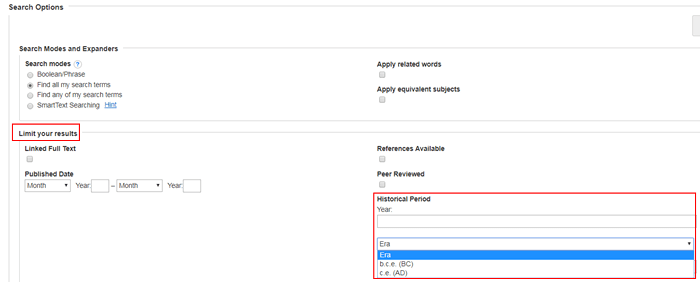

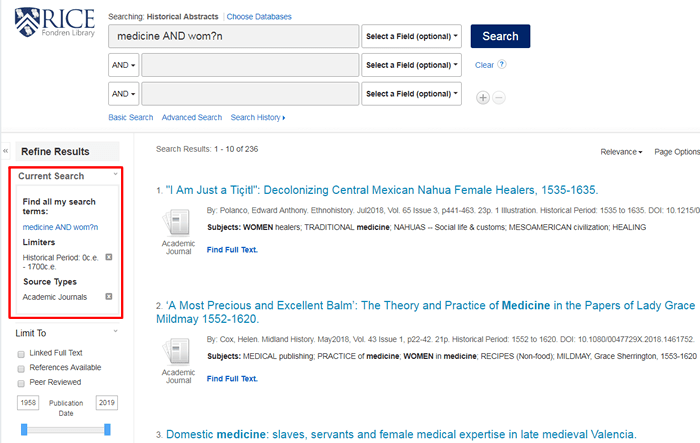

In most ways, Historical Abstracts works like other databases. One useful feature is the “Historical Period” limiter under “Limit your results.” Enter a numeric year and select an “era”, for example, 750 b.c.e. (BC) to 500 c.e. (AD). To access this feature, scroll down on the database’s search page after you enter your keywords.

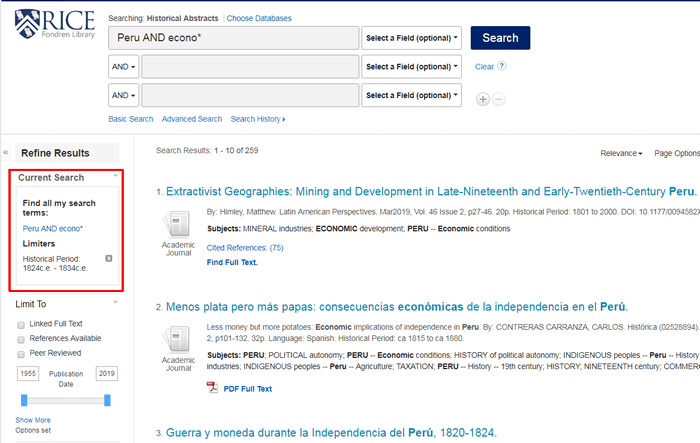

One way to use this feature is when you’re looking for information about a certain period in a region’s or movement’s history. For example, the following search is for Peru and economics during the first decade of the country’s independence. The first result is a long-range article that appears to focus more heavily on a later period, but the second and third results pertain to the economy of Peru during early independence.

Another potential use for this feature is early in research, when you have a general topic and time period, but haven’t narrowed down which region or aspect of that topic you specifically want to focus on. The following search is for women and medicine before 1700, and the first three results pertain to various aspects of that topic.

PsycINFO

PsycINFO indexes resources in the field of psychology, especially behavioral science and mental health, as well as related fields, such as psychiatry, sociology, education, and linguistics.

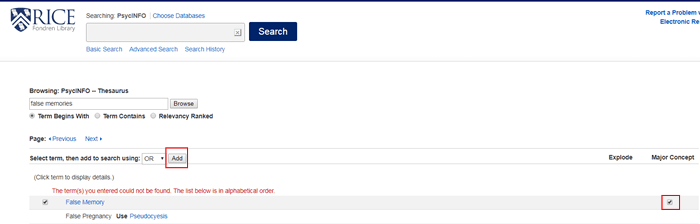

PsycINFO’s most powerful searching features–its subject headings and its extensive options to refine results–have been discussed above. Combining PsycINFO’s subject headings with its refinement options is a good way to search the database. The following is a walkthrough of a search for false memories that occur in elderly adults.

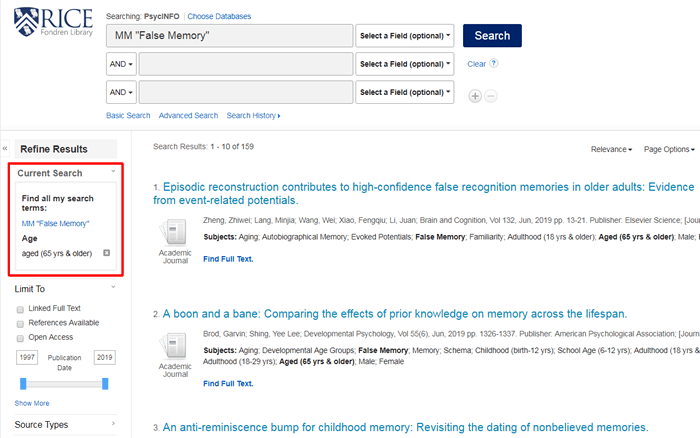

In this case, a search for “false memories” in PsycINFO’s thesaurus reveals the subject heading is “False Memory.” “False Memory” is checked as a Major Concept to avoid results that only briefly touch on the topic and searched.

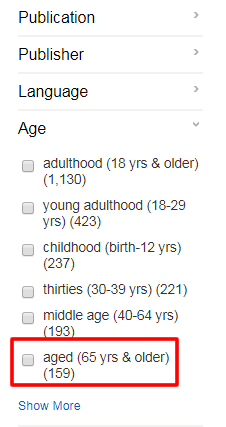

Next, the results are narrowed to materials that discuss the topic in adults aged 65 and older using the facets on the left side of the page, and potentially useful search results are obtained.

PubMed

PubMed is a database of millions of citations of resources, primarily journal articles, in the health sciences and life sciences. As discussed above, PubMed has an extensive system of subject headings. However, use of PubMed’s subject headings are not required for all basic searches. The two searches below are for the same topic, medications for narcolepsy, with and without PubMed’s subject headings.

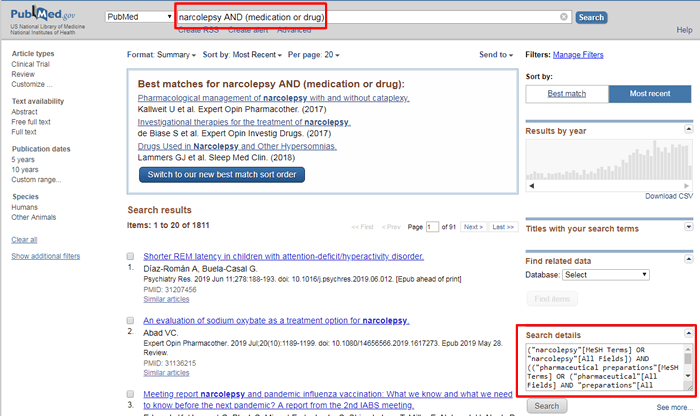

The first search is for narcolepsy and medications or drugs without use of PubMed’s medical subject headings (MeSH). Of the first several results, only the second clearly relates to the use of medications to control narcolepsy.

To the right of the results is a “Search details” box. Here, you can see that PubMed automatically mapped “narcolepsy” to the corresponding subject heading, as well as searches for it in all fields of citations. It also mapped “medication” to “pharmaceutical preparations” and searched for the words “pharmaceutical,” “preparation,” “medication,” and “drug” in all fields of citations. If any PubMed search doesn’t return the types of results you expect, the Search details box is a good place to check to see what PubMed did with your keywords.

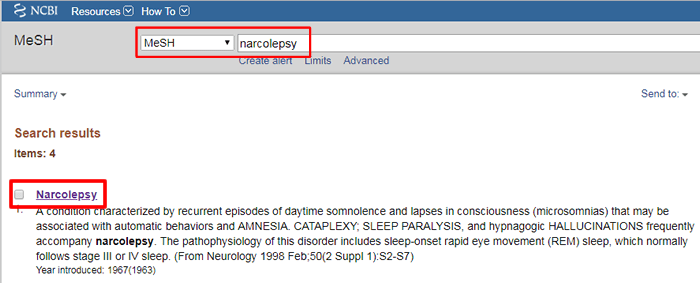

Now, let’s try a search for medications for narcolepsy using the medical subject headings (MeSH). First is a search for MeSH terms related to “narcolepsy.” “Narcolepsy” appears as a term itself.

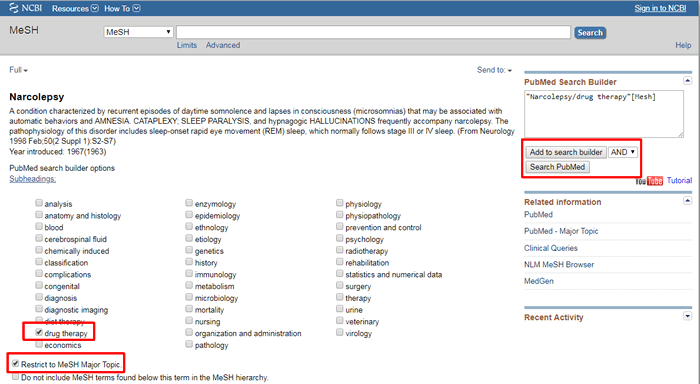

From the “Narcolepsy” subject heading page, “Drug therapy” is selected as subheading so that results focus on medications for narcolepsy, not the diagnosis, prevention, history, or other aspects of the condition, and the “Restrict to MeSH Major Topic” box is checked so that all results primarily discuss drug therapy for narcolepsy.

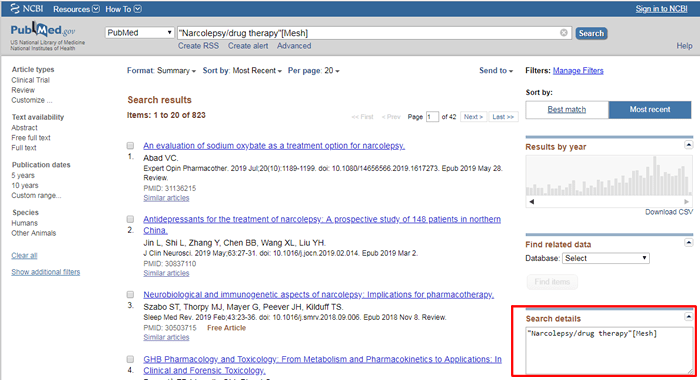

These specifications are then added to the PubMed Search Builder at the right, and the search is run. The top results are clearly relevant. PubMed searches for alternative terms based on MeSH automatically.

Altough, for this search, using subject headings produced more relevant results more quickly, you may not always want to rely on PubMed’s medical subject headings (MeSH). Medical subject headings are assigned by human indexers, and most PubMed articles do not receive subject headings until about a year after they are entered into the database. For very recent materials, then, keyword searches are most likely to produce the results you need.

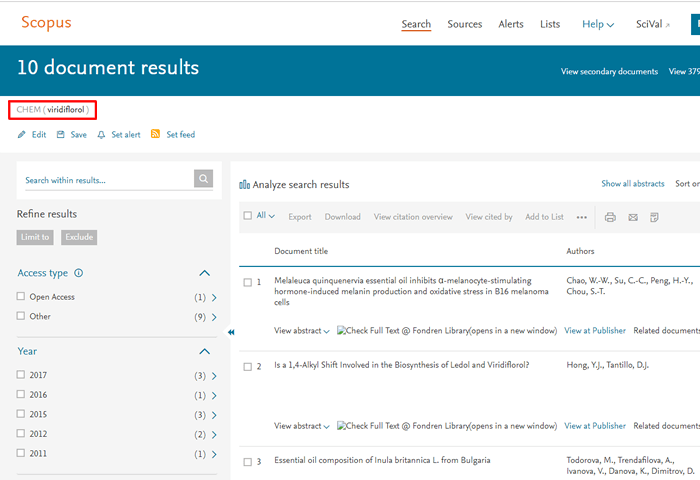

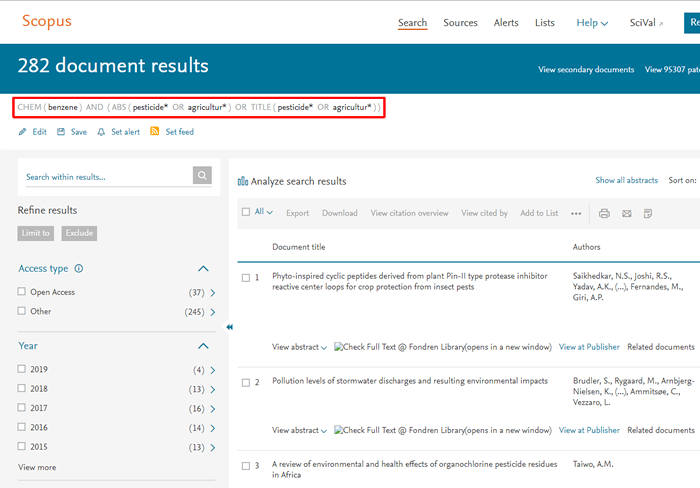

Scopus

Scopus indexes thousands of journals, as well as webpages, and covers physical sciences, life sciences, health sciences, social sciences, and U.S. and international patents.

Scopus works very similarly to other databases, but it has some specialized filters (called Field codes) in its Advanced search that can be used to refine results. For example, you can search for amino acids or nucleotides by sequence numbers, chemical entities by CAS name and/or CAS registry number, and conferences by name, location, or sponsors.

Click on any field code to see an explanation of what to use it for and an example of how to enter it into a search.

Below are two example searches using the CHEM field code. The first is for viridiflorol, an uncommon compound. The second is more benzene, a very common compound, and includes additional search terms with their own Abstract and Title field codes to narrow the search.

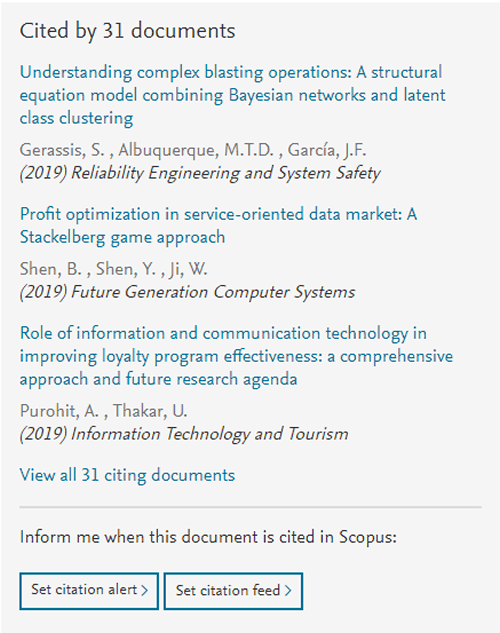

One very useful feature in Scopus is the “Cited by” list. Found on the right side of each article’s record, this list provides citations and links to later articles that cited the article in question.

Web of Science

Web of Science indexes journals, books, and conference proceedings across disciplines, including the sciences, social sciences, arts, and humanities.

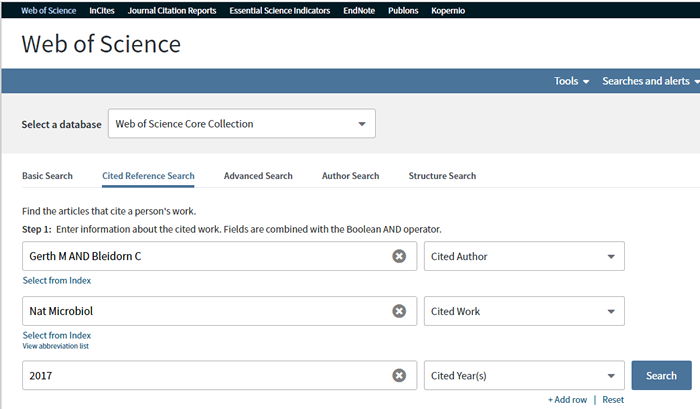

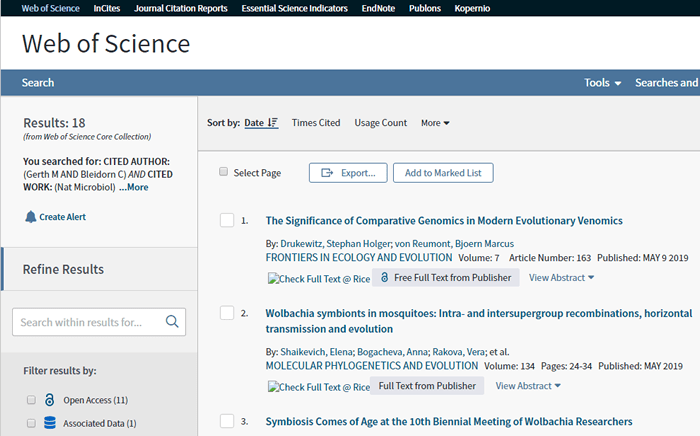

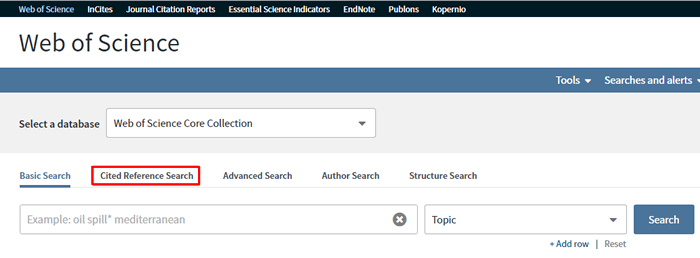

Web of Science’s basic search function operates like that of other databases, and its Advanced Search offers field tags similar to but more limited than those found in Scopus. One of Web of Science’s unique features is its ability to perform Cited Reference, or citation, searches. Citation searches are useful for seeing how scientific research and other scholarly conversations build on each other, and can help you see the impact a particular article as had on its field.

The following is an example of a Cited Reference search performed on a 2017 article about Wolbachia bacteria from Nature Microbiology.